“People describe it as someone’s personality changing, but I don’t like to think of it like that. I like to think of it as they’re desperately trying to hold on to what they’ve got. It must be so scary to not remember a person, or not remember what you were going to say, or what you were going to do, where you were going to go.”

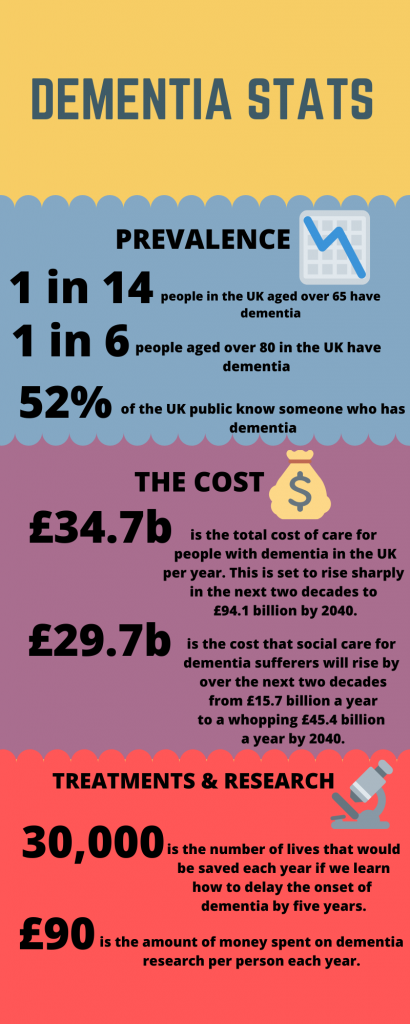

The words of Lorna Robertson to describe her sister to sum up the reality for people all over the UK. Dementia is the biggest killer in the country, and there are an estimated 850,000 people living with the condition. With a rising population, this number is set to increase to one million by 2025, and to two million by 2050.

For any family member, witnessing a loved one mentally deteriorating is a very distressing experience, but Lorna Robertson had to go through this twice. Her mother became diagnosed with the condition back in the 1980s, and after she died she had to relive the experience again when her older sister Pat developed the condition in 2013.

Lorna recalls the first time she noticed her sister changing. “I think probably the first symptoms of her having dementia were she just went incredibly quiet. Rather than say the wrong thing or do the wrong thing she just didn’t do anything, so she stopped really. She would just sort of answer yes, no- polite answers rather than instigate a conversation, and that was where we all started noticing things were probably changing.”

Dementia is a progressive condition, with symptoms worsening over time. It can sometimes take years to reach the stage where you need professional care. This was the case for Pat, a former care home worker, who experienced the condition gradually worsening over a long period of time.

Her daughter Lorna explains: “Her symptoms evolved really gradually, and it’s interesting because I’ve worked with people with dementia for 19 years this year, and the amount of times carers have said to me, ‘I can see back now, like two years ago or a year ago when he did that thing, got lost in the car, or do whatever, that was the start of it.’ But I think it really just builds so slowly that you don’t notice it.”

People with dementia have to go through many challenges on a daily basis, and for those who live in their own home, it can be a difficult experience gradually losing the ability to do menial tasks that many of us do without thinking, which is what Lorna saw happening to her sister.

“When she was living alone, what was a challenge for her was just day to day stuff, remembering where to go, remembering what to do, remembering to go and buy food, remembering then what to do with it, or buy the right food, that kind of thing. Just remembering who people were. I think it really is the day to day things, all the stuff we absolutely take for granted- making a cup of tea, just being able to use things like the microwave”, Lorna explains.

“Then just before she went into a care home she didn’t recognise where she lived. She no longer recognised it as home, and she would say things like, ‘where do I sleep?’, ‘when am I going home?’, so how scary must that be, when you’re in a place on your own and you don’t recognise it as home (sic)?”

After a number of years of living in her own home, Pat was moved to a care home in 2018, which happened to be the place that she worked in before getting dementia.

One thing Lorna finds hard is being able to spend time with her sister as a family outside of the care home, and explains that Pat now finds that she can no longer do the activities she used to enjoy before developing the condition.

“I think what’s hard now is when we take her out of the care home or if she comes out of the care home she’s so scared. She just wants to be back there because that’s where she feels safe, and she’ll say things like ‘I need to get back now’, so you’ve almost lost all that quality time, the things that you potentially could’ve done, like gone shopping. She used to be in town every day, she loved Marks and Spencer’s… but none of that she can do anymore and you know that if she didn’t have dementia that’s what she would be doing… although she’s happy in herself now because she feels safe and she’s in a care home that is lovely and she feels comfortable with, you know it’s all the things that she is missing out on, and you’re missing out on with her as well.”

The bigger picture

Although steps are being made to combat the issue of dementia, there is still a long way to go. Funding is one area which is lacking in this field. UK dementia research charities funded approximately £23 million of research in 2015/16, compared to £310 million for charity research funding for cancer.

Professor Gordon Wilcock, Founder Chairman of the Alzheimer’s Society, believes that those in power need to be contributing more towards dementia research.

He explains: “If you look at the research side of things, in the dementia field we only have about a third of the funding that cancer research gets from the government.

“They should be putting a lot more money into research, and I think this research should be directed in two directions. One is scientific research to develop better ways of treating people with dementia, because we don’t have very good treatments.

“But the other area is to say it might take many years for a new drug that’s discovered to actually get into use, but there are lots of people out there with dementia who need care at the moment so I think quite a lot of research should go into trying to evaluate the best ways of providing care to people who’ve got dementia so you can actually help them now.”

The quality of care is an area which Professor Wilcock believes is not up to scratch, and needs to be improved, as well as distributed evenly across the UK.

He said: “We need much better quality of care universally, there’s still a very big postcode lottery so if you live in the area of one health authority you’ll get one range of things available, if you go somewhere else you’ll get another, and it’s often better in some places than others.

“It isn’t just medical care, it’s also social care, and the most important thing is to help people live in their own homes for longer, and the reason for that is because it’s much less expensive to keep people in their own homes. But the most important reason to me is that people prefer to be in their own homes.”

Care homes and day centres who help look after dementia patients are currently unable to support all those with dementia due to a lack of money and resources. Karen Cockram, a care worker who works in a day centre in Gloucestershire explains: “To be honest, there’s not enough places for them to go. We get them twice a week, they try to keep them on the same days, so they come to us on the same days so they’re all more or less together. But their funding gets cut, their families are desperate for help, and there’s no money to help them. Some are often just sat at home because they haven’t got any funding or they haven’t got any money to go anywhere or to get respite care.”

The current system for social care means that people who have more than £23,250 in savings, which includes the value of their home, is rejected for state-funded care, and has to pay for themselves.

Karen Cockram believes those in power should be doing more to improve the care sector. She said: “They should be providing more places, more homes that are geared up for dementia patients… and loads more carers. We struggle, and I think the care homes in general at the moment are struggling to get staff. I know we are particularly and our wages aren’t brilliant. I don’t know whether people don’t come because of the money side of it or whether it’s the hours. They need to provide more carers. There should be more money put into social care than there is now.”

While the stigma around psychiatric illnesses, in particular dementia, is starting to go, education on dementia is one area which Professor Wilcock believes could be improved to create a society that knows how to deal with those with the condition.

He said: ” I think we need much bigger education programmes…perhaps we should start in primary schools, and some primary schools have done this, so that children learn about dementia. And if society can then accept this then it means your natural reaction when you see someone’s got a problem is to help them, whereas at the moment the natural reaction is to be crossly impatient if someone’s taking longer or getting in your way. I think society needs to be prepared to learn about dementia and moderate its behaviour in relation to the needs of people with dementia.”

At the moment the drugs on offer for those with Alzheimer’s disease, which is the most common form of dementia, are used to treat the symptoms of the illness. These are called symptom-modifying drugs, however what scientists are trying to find are drugs which stop the brain cells from dying, which are called disease-modifying drugs. Professor Wilcock believes that we haven’t yet been able to find a cure because we’ve got the wrong idea of Alzheimer’s disease.

He explains: “Everyone expects there to be a magic bullet that’s going to go and sort out what’s going on in the brain, but I think there are so many different factors causing Alzheimer’s Disease…. both genetic and environmental that determine whether a person gets Alzheimer’s, but they’re not all going to be the same in every person, so trying to find one drug that’s going to affect and improve everybody, it’s technically feasible, but in practice it’s very difficult to do that.”

Although the numbers of people in the country with dementia are rising and a cure for the illnesses behind the condition look far away, there are organisations out there championing all those with dementia who need help. The Alzheimer’s Society, for example is one of the UK’s leading dementia charities. They are the only charity in the country that are investing in research into dementia care, cause, cure and prevention. They provide over 3000 local support services across England, Northern Ireland and Wales which offer information, care and support to people with dementia, their families, friends and carers.

The charity also campaigns for the rights of everyone affected by the condition, to ensure that dementia is at the top of the political agenda, and raise awareness so that society is more understanding so those with dementia can live without fear or prejudice.

One of their biggest campaigns is ‘Dementia Friends’, where the general public can learn about the condition, so they are more aware of what dementia is and how to interact with and support those with dementia. Since 2017 more than two million people have signed up to become dementia friends. So while the condition isn’t going away anytime soon, it’s good to know there are those out there who are fighting for a society which is there for those with dementia.

The lasting message that Lorna Robertson wants people to know is that no matter how dementia might affect your life, you are still the same person deep down.

“I think once you get that diagnosis, you’re the same person as the day before you had that diagnosis”, she explains.

“Nothing’s changed in that respect, other than you can now start to understand the situation, perhaps talk to someone about it, get some emotional support, and also get some practical support if need be.”

To learn more about dementia and the support services out there visit the NHS website: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dementia/

For more information about dementia and the work the Alzheimer’s Society do, visit their website: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/

To find out more about the ‘Dementia Friends’ scheme click this link: https://www.dementiafriends.org.uk/